Chameleons (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae) in the Islamic Golden Age: Zoological Observation, Intellectual Transmission, and Cultural Meaning

by Petr Necas

By Petr Necas

Abstract

This study reconstructs the zoological, philosophical, and symbolic treatment of chameleons (al-ḥarbāʾ, الحرباء) in classical Islamic sources, focusing on the works of Al-Jāḥiẓ and Avicenna, and extending to al-Damīrī, al-Qazwīnī, and the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ. Through original Arabic citations, historical biogeography, and cultural analysis, we explore how Islamic scholars engaged with the chameleon as both a natural phenomenon and a metaphysical symbol. Qur'anic verses concerning divine signs (āyāt), animal purpose, and cosmological order are examined to contextualize the chameleon within broader Islamic conceptions of nature and revelation. The study also speculates on the species these scholars may have observed, considering trade routes, ecological shifts, and textual evidence. The result is interdisciplinary, fusing zoology, philology, intellectual history, and cultural anthropology.

Keywords: Chameleon, Islamic zoology, Al-Jāḥiẓ, Avicenna, al-Damīrī, al-Qazwīnī, Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ, Kitāb al-Ḥayawān, Kitāb al-Shifāʾ, Arabic zoological texts, historical biogeography, caravan trade, metaphysics, invisibility, āyāt, Qur'anic cosmology, animal symbolism

The Chameleon in the Qur'an and Islamic Sacred Texts

Despite the Qur'an's extensive engagement with the animal world, over 200 verses mention animals explicitly, the chameleon (al-ḥarbāʾ, الحرباء) is not named directly in the Qur'anic text. However, its symbolic attributes, camouflage, transformation, and concealment, align with broader Qur'anic themes of divine signs (āyāt), hidden knowledge, and the variability of creation. This chapter explores how the chameleon's characteristics resonate with Qur'anic motifs and examines its indirect presence in exegetical and theological discourse.

Qur'anic Framework: Animals as Signs

وَمَا مِن دَابَّةٍ فِي الْأَرْضِ وَلَا طَائِرٍ يَطِيرُ بِجَنَاحَيْهِ إِلَّا أُمَمٌ أَمْثَالُكُم "There is no creature on the earth or bird that flies with its wings except [that they are] communities like you." (Surah Al-Anʿām 6:38)

This verse affirms that animals possess communal structures and divine purpose, inviting humans to contemplate their place in creation. Though the chameleon is not named, its behavioral traits, adaptive coloration, slow movement, and elusive presence, embody the kind of natural wonder the Qur'an urges believers to reflect upon.

Symbolic Parallels: Concealment and Revelation

The chameleon's ability to change color and blend into its environment evokes Qur'anic themes of concealment and revelation. The concept of al-ẓāhir wa-l-bāṭin (the manifest and the hidden) appears in multiple verses:

هُوَ الْأَوَّلُ وَالْآخِرُ وَالظَّاهِرُ وَالْبَاطِنُ "He is the First and the Last, the Manifest and the Hidden." (Surah Al-Ḥadīd 57:3)

This metaphysical duality mirrors the chameleon's physical transformation and invisibility. In Islamic theology, such qualities are often interpreted as reflections of divine attributes, multiplicity within unity, presence within absence.

Exegetical Mentions and Later Commentaries

While classical tafsīr literature does not mention the chameleon by name, later zoological and magical treatises, such as al-Damīrī's Ḥayāt al-Ḥayawān, incorporate it as a creature with symbolic and medicinal properties. These texts often draw upon Qur'anic language to frame their descriptions, treating the chameleon as one of the āyāt al-khalq (signs of creation).

Al-Damīrī writes:

الحرباء حيوان عجيب، يتلون بألوان مختلفة، ويُقال إنه يُستخدم في الطب والسحر، وله خصائص في دفع العين "The chameleon is a wondrous animal, changing into various colors. It is said to be used in medicine and magic, and has properties in repelling the evil eye." (Al-Damīrī 1906: pp. 134–136)

This framing echoes Qur'anic descriptions of animals as beneficial and purposeful, even when their functions are not immediately apparent.

Theological Implications

The Qur'an also emphasizes that God creates creatures beyond human knowledge:

وَيَخْلُقُ مَا لَا تَعْلَمُونَ "And He creates that which you do not know." (Surah Al-Naḥl 16:8)

This verse legitimizes the inclusion of lesser-known or regionally obscure animals, such as the chameleon, within the Islamic cosmological imagination. It affirms that divine creation is vast, layered, and not limited to the familiar.

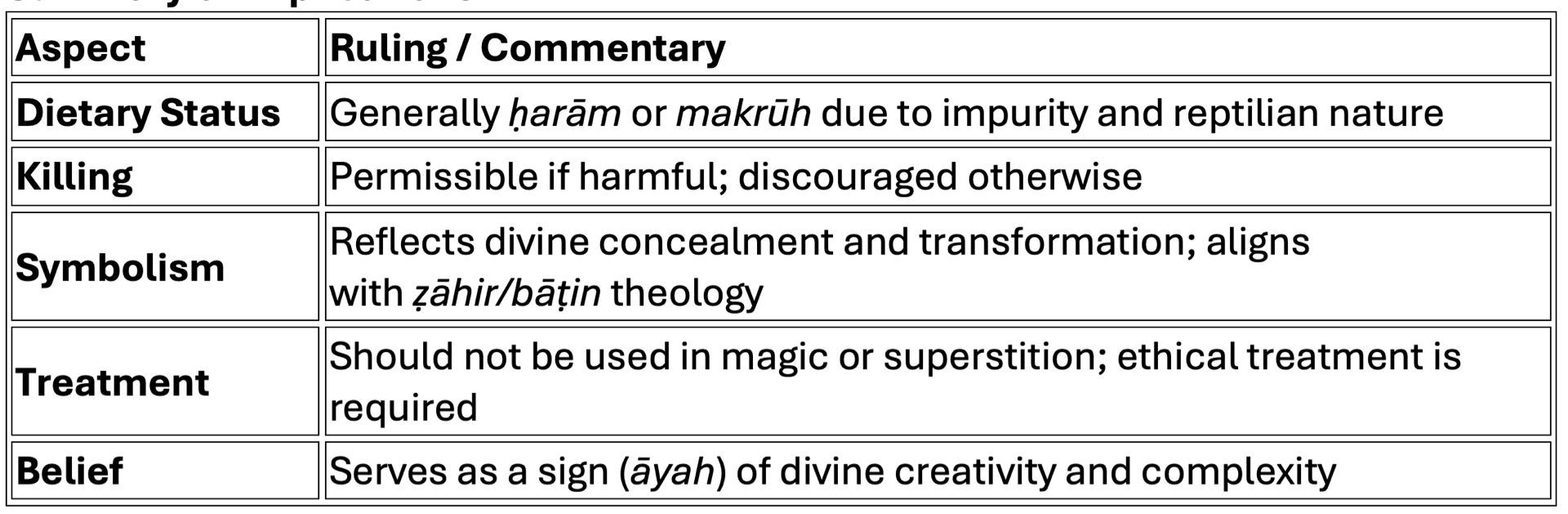

Legal and Ethical Classification of the Chameleon

In Islamic jurisprudence, animals are classified based on their purity, danger, and utility. The chameleon, being a carnivorous reptile, is generally grouped with lizards and salamanders. This has implications for diet, treatment, and rulings on killing.

Killing the Chameleon

While the Qur'an does not legislate directly on the chameleon, Hadith literature provides guidance on similar creatures. A well-known Hadith states:

"مَنْ قَتَلَ وَزَغًا فِي أَوَّلِ ضَرْبَةٍ فَلَهُ كَذَا وَكَذَا حَسَنَةٌ..." "Whoever kills a gecko with the first strike will receive such-and-such reward…" (Sahih Muslim)

Though this refers to the gecko (wazagh), scholars often extend its permissibility to similar species, including the chameleon, especially when considered harmful or impure. Hanafi scholars note:

"If one is in danger from a harmful animal and fears attack, then he may kill it." (Darul Ifta Birmingham)

Thus, the chameleon may be killed if it poses a threat or is considered impure, but not arbitrarily or for sport.

Dietary Rulings

Islamic dietary law classifies the chameleon as ḥarām or makrūh due to its reptilian nature and carnivorous habits:

وَيُحَرِّمُ عَلَيْهِمُ الْخَبَائِثَ "And He forbids them the impure things." (Surah Al-Aʿrāf 7:157)

Reptiles like snakes, lizards, and chameleons fall under al-khabāʾith (impure things), and are excluded from permissible food categories in most schools of thought.

Beliefs and Treatment

Islamic ethics emphasize compassion toward animals:

مَنْ رَحِمَ حَتَّى الذَّبِيحَةَ رَحِمَهُ اللَّهُ "Whoever shows mercy even to the slaughtered animal, Allah will show him mercy." (Musnad Ahmad)

While harmful animals may be killed, Islam prohibits cruelty or unnecessary harm. The chameleon, if not dangerous, should be left unharmed. Using it in folk medicine or magic, as noted in al-Damīrī's Ḥayāt al-Ḥayawān, is discouraged unless supported by legitimate medical evidence.

Summary of Implications

Al-Jāḥiẓ: Life, Travels, and Zoologcal Exploration

Abū ʿUthmān ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī (c. 776–868 CE) was born in Basra, a city rich in marshland biodiversity. He studied under Muʿtazilī theologians and grammarians, later moving to Baghdad, the Abbasid capital, where he engaged with the Bayt al-Ḥikma (House of Wisdom). His travels likely included Syria, exposing him to Levantine fauna.

Al-Jāḥiẓ's zoological method combined:

- Direct observation

- Compilation of oral reports

- Integration of Greek sources (especially Aristotle's Historia Animalium)

- Theological reflection

His magnum opus, Kitāb al-Ḥayawān, spans seven volumes and includes detailed accounts of animal behavior, morphology, and symbolism. He mentions mechanisms that centuries later were defined as evolution or mimicry.

Arabic Citation from Kitāb al-Ḥayawān:

الحرباء دابة تتلون ألوانًا مختلفة، وتكاد لا تُرى إذا كانت على الشجر، لكثرة شبهها بورقها. وهي تأكل الهواء، وتُقال إنها لا تشرب الماء.

Translation:

"The chameleon is a creature that changes into various colors and is nearly invisible when on trees, due to its resemblance to the leaves. It feeds on air, and it is said that it does not drink water."

Commentary:

Al-Jāḥiẓ's invisibility motif aligns with Islamic metaphysical ideas of al-ẓāhir wa-l-bāṭin (the manifest and the hidden). His claim that the chameleon "feeds on air" echoes Aristotelian zoology, which described animals with minimal bodily needs. Aristotle writes:

"The chameleon feeds on air and occasionally insects, and its color changes with its surroundings." (Historia Animalium, Book II, 9)

Al-Jāḥiẓ likely accessed Aristotle through Arabic translations by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq and his circle.

Avicenna: Life, Travels, and Scientific Integration

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā (980–1037 CE), known as Avicenna, was born in Afshana near Bukhara. His intellectual career spanned Rayy, Hamadan, and Isfahan. As a physician, philosopher, and polymath, he synthesized Aristotelian science with Islamic metaphysics.

His zoological remarks appear in:

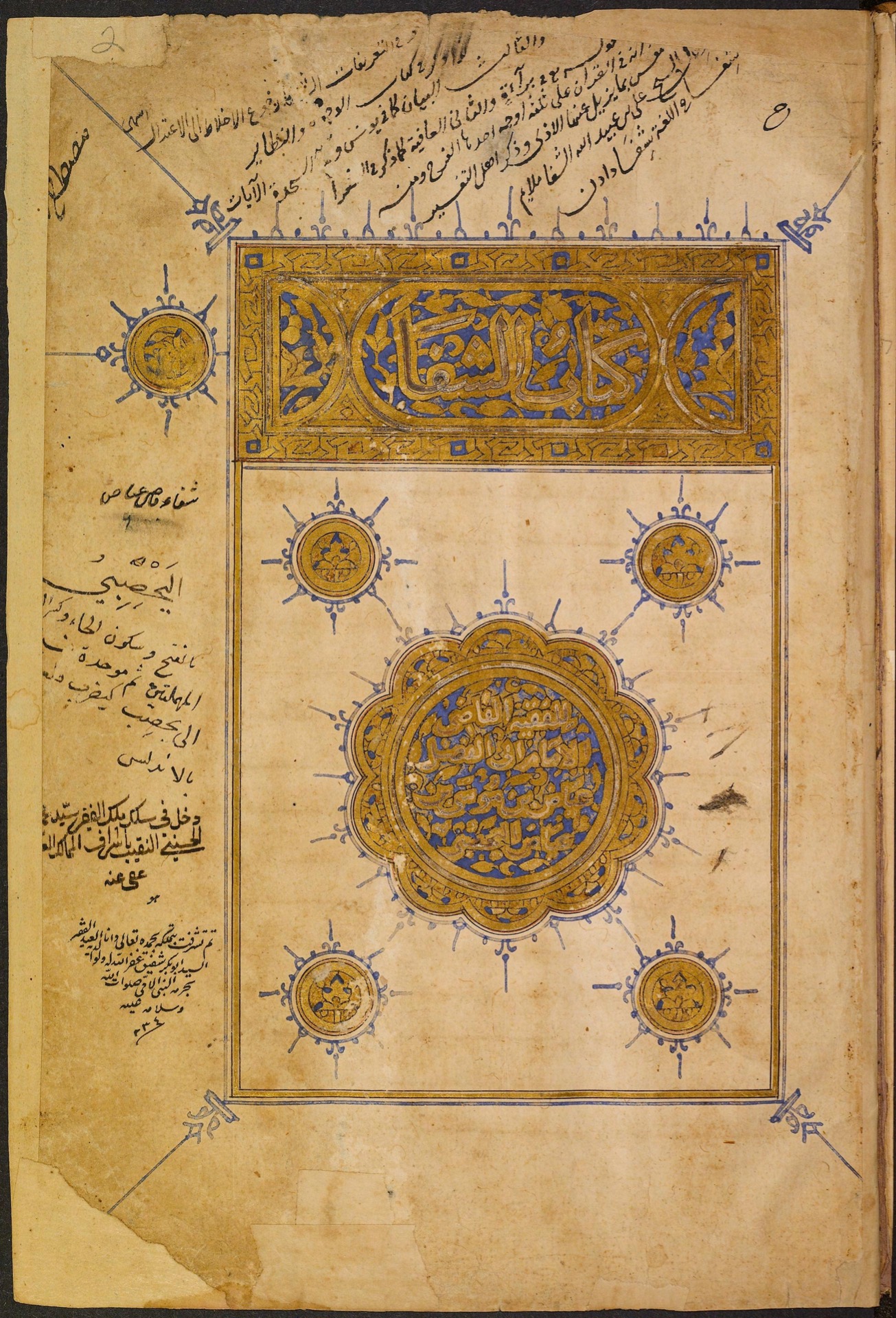

- Kitāb al-Shifāʾ (Book of Healing)

- al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb (Canon of Medicine)

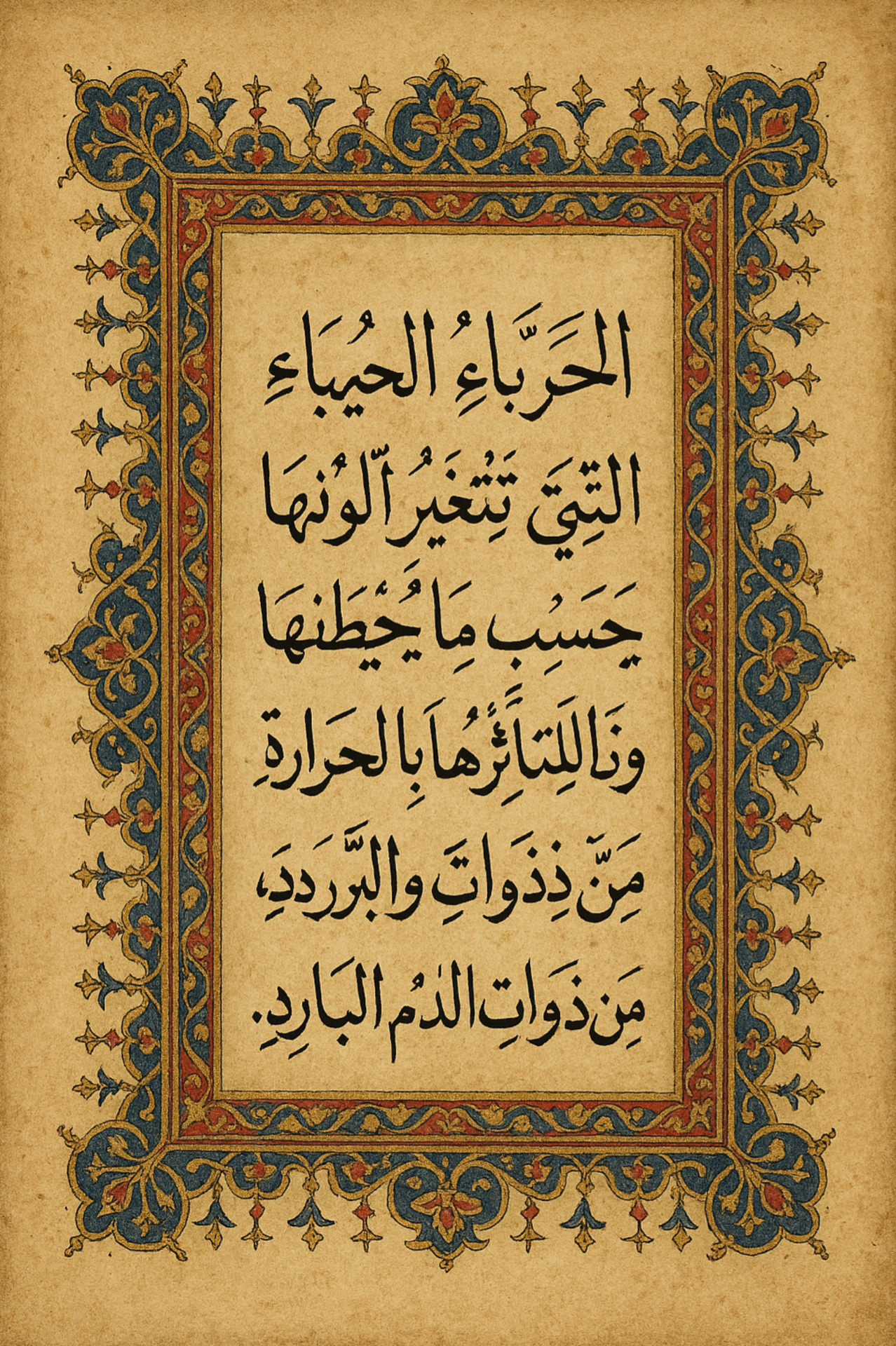

Arabic Citation from Kitāb al-Shifāʾ:

الحرباء من الحيوانات التي تتغير ألوانها بحسب ما يحيط بها، وذلك لتأثرها بالحرارة والبرودة، وهي من ذوات الدم البارد.

Translation:

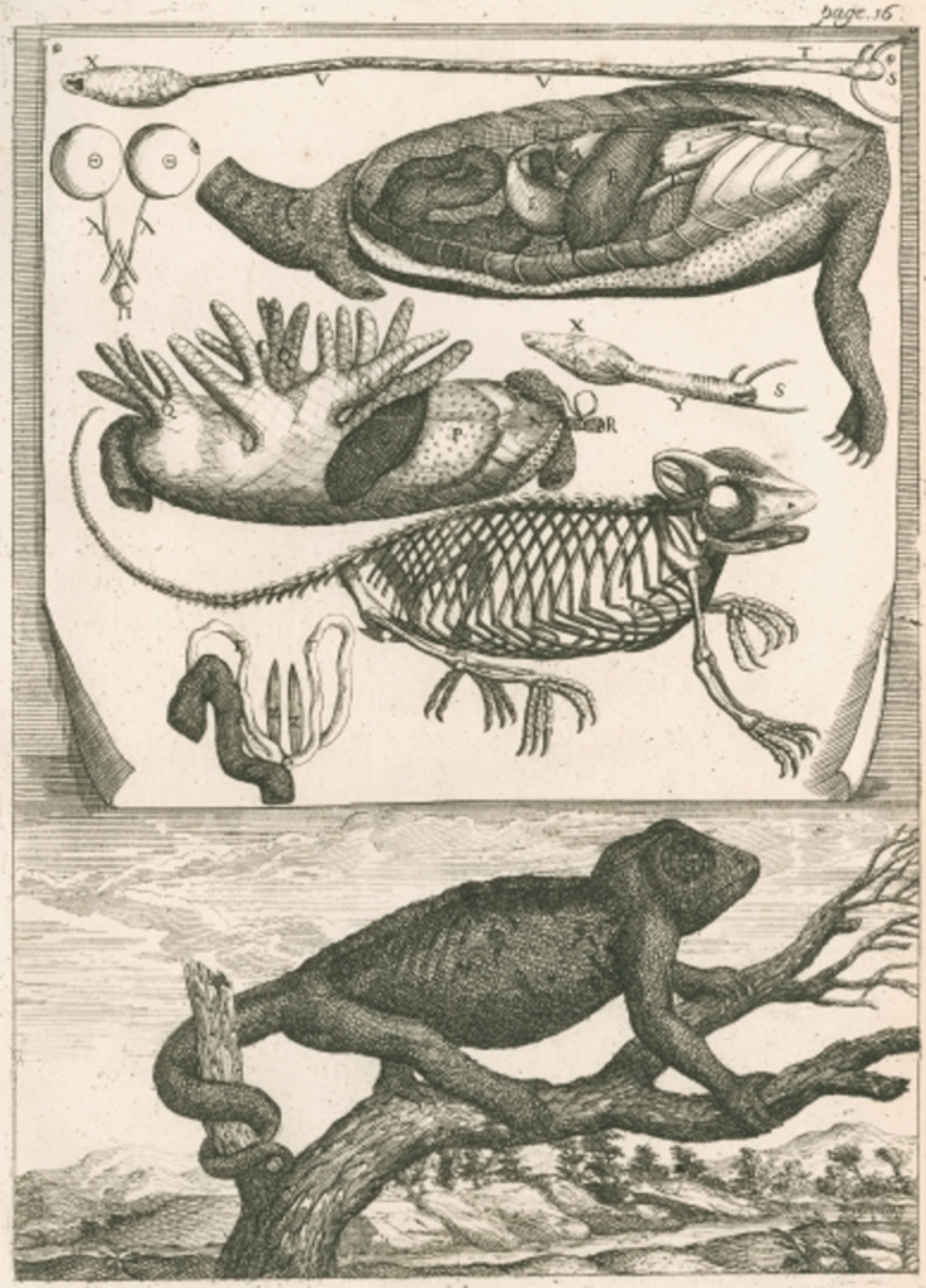

"The chameleon is among the animals whose colors change according to their surroundings, due to its sensitivity to heat and cold. It is among the cold-blooded creatures."

Commentary:

Avicenna's classification of the chameleon as "cold-blooded" anticipates modern taxonomy. His physiological framing avoids folkloric embellishment, favoring empirical reasoning. His access to Aristotle's Historia Animalium was mediated through Arabic translations and commentaries.

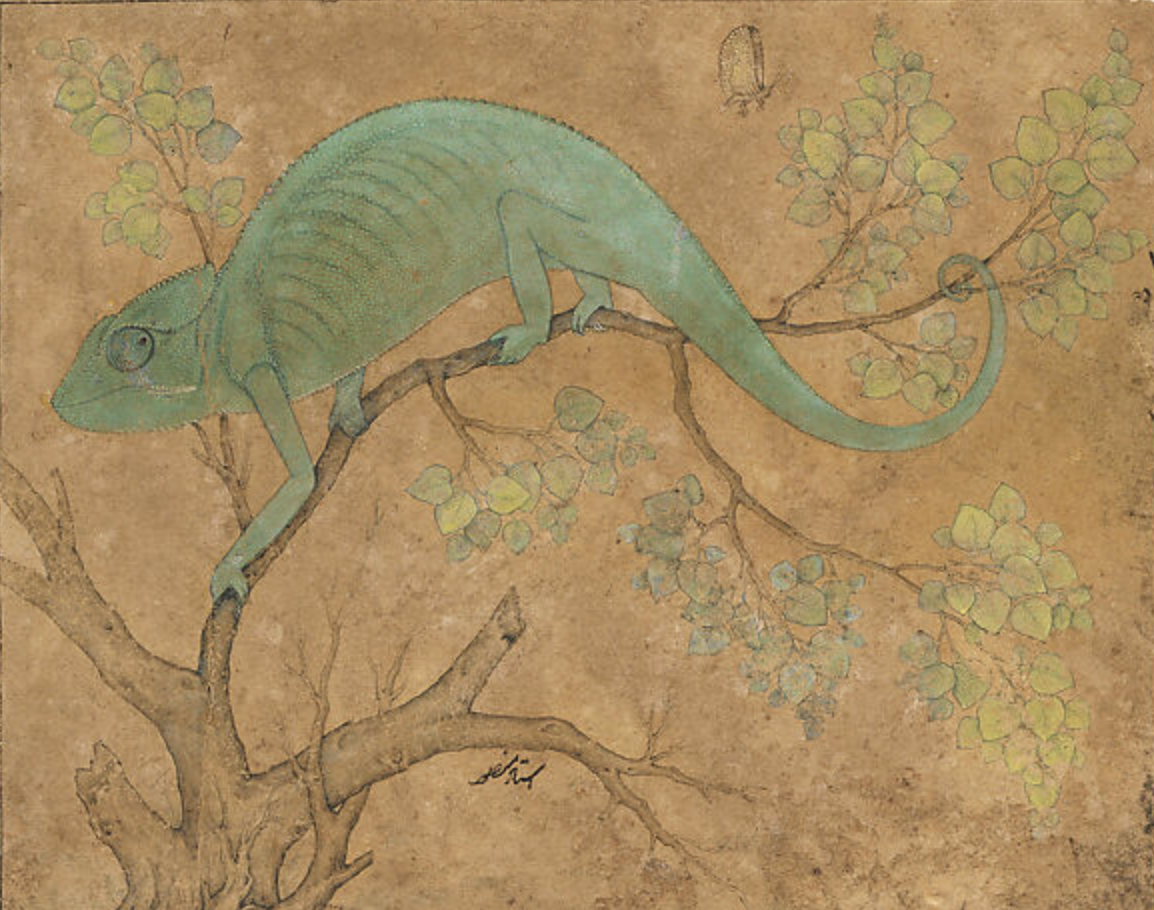

Possible Species Assignment and Historical Biogeography

Local Observation vs. Caravan Acquisition

Given ecological shifts since the 9th–11th centuries, the species observed by Al-Jāḥiẓ and Avicenna may differ from current distributions. Aridification of Mesopotamia and Persia has altered habitats. Chameleons may have been:

- Locally observed in marshes, woodlands, or gardens

- Acquired via caravan trade from Yemen, Oman, Syria, Egypt, or Asia Minor

Trade Routes and Species Possibilities

Region of Origin

Trade Route

Possible Species

Syria

Levantine corridor

Chamaeleo chamaeleon recticrista

Yemen/Oman/Saudi Arabia

Southern Frankincense Route

Chamaeleo arabicus, C. calcarifer, C. calyptratus, C. chamaeleon orientalis

Asia Minor

Anatolian route

C. chamaeleon recticrista

Egypt/Nile Delta

Red Sea–Mediterranean trade

C. africanus (also introduced to Peloponnese), C. c. chamaeleon

Genetic studies confirm that C. africanus populations in southern Greece share mitochondrial markers with Nile Delta populations, suggesting human-mediated introduction via trade or curiosity transport.

Beyond Revelation: Chameleons in Islamic Theology, Mysticism, and Science (Chronological Survey)

This chapter traces the symbolic, empirical, and metaphysical treatment of the chameleon (al-ḥarbāʾ, الحرباء) in Islamic texts beyond the Qur'an and canonical zoological works. Each entry includes the original Arabic citation, precise translation, interpretive commentary, and bibliographic reference. The examples are listed chronologically to highlight the evolution of ideas across centuries.

Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ (10th century CE / ca. 980 CE)

Rasāʾil Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ, Epistle 22: "On Animals"

Arabic citation: الحرباء حيوان يتلون بلون ما يجاوره، وهو في ذلك مثال على التلون النفسي والتقلب في الآراء.

Translation: "The chameleon is an animal that takes on the color of what surrounds it, and in this it is an example of psychological changeability and fluctuation in opinions."

Commentary: Used allegorically, the chameleon becomes a moral metaphor for intellectual instability. The Ikhwān's philosophical zoology blends empirical observation with ethical critique. (Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ1957)

Al-Bīrūnī (11th century CE / ca. 1030 CE)

al-Tafhīm li-Awāʾil Ṣināʿat al-Tanjīm

Arabic citation: الحرباء تتأثر بالحرارة والبرودة، وتغيّر لونها تبعاً لذلك، مما يدل على دقة تفاعلها مع الطبيعة.

Translation: "The chameleon is affected by heat and cold, changing its color accordingly, which indicates its precise interaction with nature."

Commentary: Al-Bīrūnī's note reflects early environmental physiology. Though brief, it shows a proto-scientific interest in adaptive mechanisms.(Al-Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān 1948)

Al-Ghazālī (11th century CE / ca. 1095 CE)

Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn, Book 1: "ʿAjāʾib al-Khalq"

Arabic citation: كل مخلوق له حكمة، والحرباء بتلونها تُذكّر بتقلب أحوال النفس، وتنوع مظاهر الخلق.

Translation: "Every creature has a wisdom, and the chameleon, with its color-shifting, reminds us of the changing states of the soul and the diversity of creation's manifestations."

Commentary: Al-Ghazālī interprets the chameleon spiritually, linking its behavior to inner transformation and divine creativity.(Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid 1966)

Ibn al-Bayṭār (13th century CE / ca. 1240 CE)

Kitāb al-Jāmiʿ li-Mufradāt al-Adwiyah wa-l-Aghdhiyah

Arabic citation: يُستعمل مسحوق الحرباء في علاج بعض الأمراض الجلدية، لما له من تأثير على لون البشرة.

Translation: "Chameleon powder is used in treating certain skin diseases, due to its effect on skin pigmentation."

Commentary: This pharmacological use reflects how the chameleon's color-changing properties were interpreted medicinally, bridging zoology and therapeutic practice.(Ibn al-Bayṭār, Ḍiyāʾ al-Dīn 1874)

Ibn ʿArabī (13th century CE / ca. 1230 CE)

al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya, Chapter on Divine Manifestation

Arabic citation: الحرباء مثال على من يتلون في حضرة الحق، فلا يثبت له لون، لأنه في كل لحظة في تجلٍّ جديد.

Translation: "The chameleon is a symbol of one who changes in the presence of the Divine, having no fixed color, for in every moment there is a new manifestation."

Commentary: Ibn ʿArabī uses the chameleon as a mystical metaphor for tajallī (divine manifestation), emphasizing spiritual fluidity and receptivity. (Ibn ʿArabī, Muḥyī al-Dīn 1980)

Al-Qazwīnī (13th century CE / ca. 1283 CE)

ʿAjāʾib al-Makhlūqāt wa-Gharāʾib al-Mawjūdāt

Arabic citation: الحرباء حيوان عجيب، يتلون بألوان متعددة، ويُظن أنه يختفي عن الأنظار.

Translation: "The chameleon is a wondrous animal, changing into multiple colors, and it is believed to vanish from sight."

Commentary: Al-Qazwīnī emphasizes marvel and illusion, aligning the chameleon with themes of invisibility and divine mystery.(Al-Qazwīnī, Zakariyyā 1981)

Al-Damīrī (14th century CE / ca. 1371 CE)

Ḥayāt al-Ḥayawān al-Kubrā

Arabic citation: يُقال إن الحرباء تنظر إلى الشمس وتسبّحها، ولذلك كانت تُعتبر من الحيوانات المباركة عند بعض الناس.

Translation: "It is said that the chameleon looks at the sun and glorifies it, and for this reason, it was considered a blessed animal by some people."

Commentary: Al-Damīrī records folkloric beliefs, blending zoology with cultural symbolism. The chameleon's solar gaze becomes a metaphor for spiritual orientation.(Al-Damīrī, Kamāl al-Dīn 1906)

Conclusions

The chameleon in Islamic thought is not merely a zoological curiosity, it is a mirror of metaphysical inquiry, ecological awareness, and cultural transmission. Through rigorous textual analysis, historical biogeography, and interdisciplinary synthesis, this study reconstructs a nuanced portrait of how Islamic scholars engaged with the natural world. Their observations, whether empirical, symbolic, or philosophical, reveal a tradition where animals were signs (āyāt) of divine wisdom, subjects of scientific inquiry, and metaphors of spiritual truth. They have interpreted the chameleon behavior and natural history through their optics, and besides theological, medicial and mythological contexts, they correctly identified Chameleons' camouflage and thermoregulation properties and belonging to cold/blooded animals long before the western science codified them with its rigorus scientific approach.

References

Al-Bīrūnī, A. R. (1948) al-Tafhīm li-Awāʾil Ṣināʿat al-Tanjīm. Hyderabad: Dāʾirat al-Maʿārif al-ʿUthmāniyya.

Al-Damīrī, M. M. (1906) Ḥayāt al-Ḥayawān al-Kubrā. Translated by A. S. G. Jayakar. London: Luzac & Co. Vol. 1: pp. 134–136.

Al-Ghazālī, A. Ḥ. (1966) Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif. Vol. 1.

Al-Jāḥiẓ, ʿA. B. (1965) Kitāb al-Ḥayawān. Edited by ʿA. S. Hārūn. Cairo: al-Hayʾa al-Miṣriyya al-ʿĀmma li-l-Kitāb. Vol. 1: pp. 112–115.

Al-Qazwīnī, Z. M. (1981) ʿAjāʾib al-Makhlūqāt wa-Gharāʾib al-Mawjūdāt. Edited by ʿA. R. Badawī. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya. pp. 88–91.

Al-Qurʾān al-Karīm (6:38) Surah Al-Anʿām. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿrifa.

Al-Qurʾān al-Karīm (7:157) Surah Al-Aʿrāf. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿrifa.

Al-Qurʾān al-Karīm (16:8) Surah Al-Naḥl. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿrifa.

Al-Qurʾān al-Karīm (57:3) Surah Al-Ḥadīd. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿrifa.

Aristotle (1910) Historia Animalium. Translated by D. W. Thompson. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Book II: pp. 73–76.

Avicenna, A. H. A. (1999) The Physics of the Healing (Kitāb al-Shifāʾ). Translated and annotated by J. McGinnis. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press. Vol. 1: pp. 212–215.

Avicenna, A. H. A. (2005) The Canon of Medicine. Translated by L. Bakhtiar. Chicago: Kazi Publications. Vol. 2: pp. 97–99.

Darul Ifta Birmingham: Ruling on killing harmful animals. https://islamqa.org/hanafi/daruliftaa-birmingham/171100/does-islam-allow-the-killing-of-harmful-animals/

Gutas, D. (2001) Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna's Philosophical Works. Leiden: Brill. pp. 45–48.

Ibn al-Bayṭār, Ḍ. D. (1874) Kitāb al-Jāmiʿ li-Mufradāt al-Adwiyah wa-l-Aghdhiyah. Cairo: Maṭbaʿat al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī.

Ibn ʿArabī, M. D. (1980) al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya. Cairo: al-Hayʾa al-Miṣriyya al-ʿĀmma li-l-Kitāb. Vol. 2.

Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ (1957) Rasāʾil Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ wa-Khullān al-Wafāʾ. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir. Vol. 3: pp. 221–224.

Islam Stack Exchange: Chameleon and lizard rulings. https://islam.stackexchange.com/questions/43588/is-it-permissible-to-kill-a-lizard-and-other-animals-of-its-species-like-chamel

McGinnis, J. (1999) Avicenna: The Physics of the Healing. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press. pp. 33–36.

Musnad Ahmad, Hadith on mercy to animals.

Nasr, S. H. (1968) Science and Civilization in Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 149–153.

Pellat, C. (1960) "Al-Djahiz." In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Leiden: Brill. Vol. 2: pp. 385–388.

Sahih Muslim, Hadith on killing geckos.

Souami, L. (2002) Le cadi et la mouche: Anthologie du Livre des animaux. Arles: Sindbad/Actes Sud. pp. 57–60.

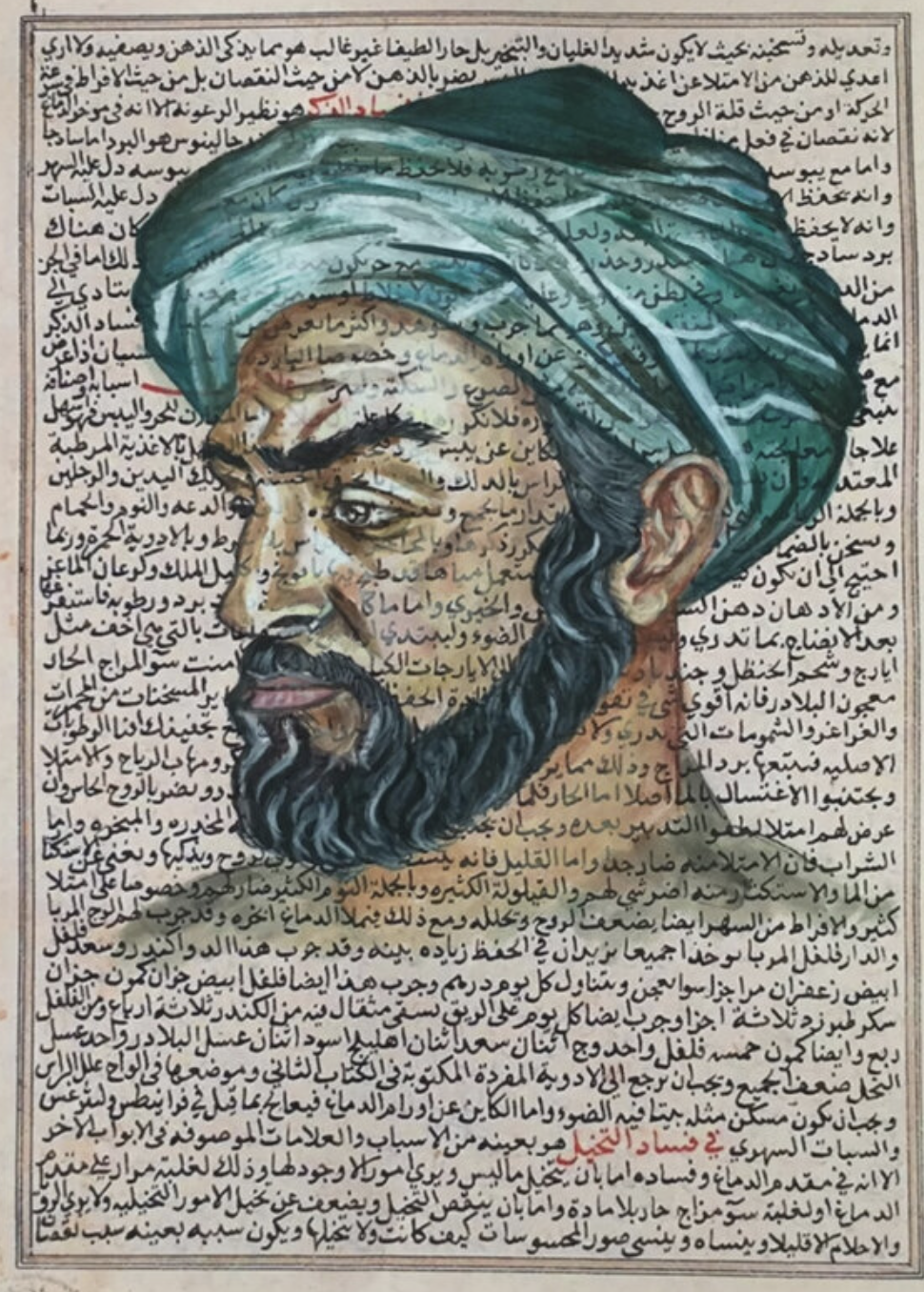

Arabic inscriptions from Kitāb al-Shifāʾ, the monumental work by Avicenna (Ibn Sina).

Manuscript from 1697 AD – A stunning copy of Kitāb al-Shifāʾ with intricate Arabic script and decorative elements.

KITAB AL-SHIFA BY AVICENNA COPIED IN 1109 AH/1697 AD

Reference: ART3002129

Arabic manuscript on paper, with 23 lines to each page written in black naskh script. Titles and catchwords in red ink. A scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, completed it around 1020, and published it. in 1027, this work is Ibn Sina's major work on science and philosophy, and is intended to 'cure' or 'heal' ignorance of the soul. Thus, despite its title, it is not concerned with medicine, contrast to Avicenna's earlier The Canon of Medicine (5 vols.) which is, in fact, medical. The book is divided into four parts: logic, natural sciences, mathematics and metaphysics. 15 by 25 cm.

Arabic Citation from Kitāb al-Ḥayawān:

الحرباء دابة تتلون ألوانًا مختلفة، وتكاد لا تُرى إذا كانت على الشجر، لكثرة شبهها بورقها. وهي تأكل الهواء، وتُقال إنها لا تشرب الماء.

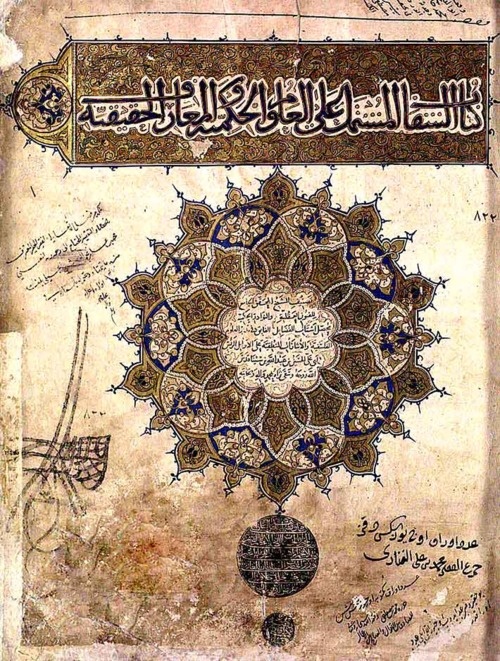

Al-Shifa bi Ta'rif Huquq al-Mustafa

Kitab Al-Shifa (The Book of Healing) by Abū Alī ibn Sīnā (1027).

Arabic Citation from Kitāb al-Shifāʾ:

الحرباء من الحيوانات التي تتغير ألوانها بحسب ما يحيط بها، وذلك لتأثرها بالحرارة والبرودة، وهي من ذوات الدم البارد.

Abū ʿUthmān ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī (c. 776–868 CE)

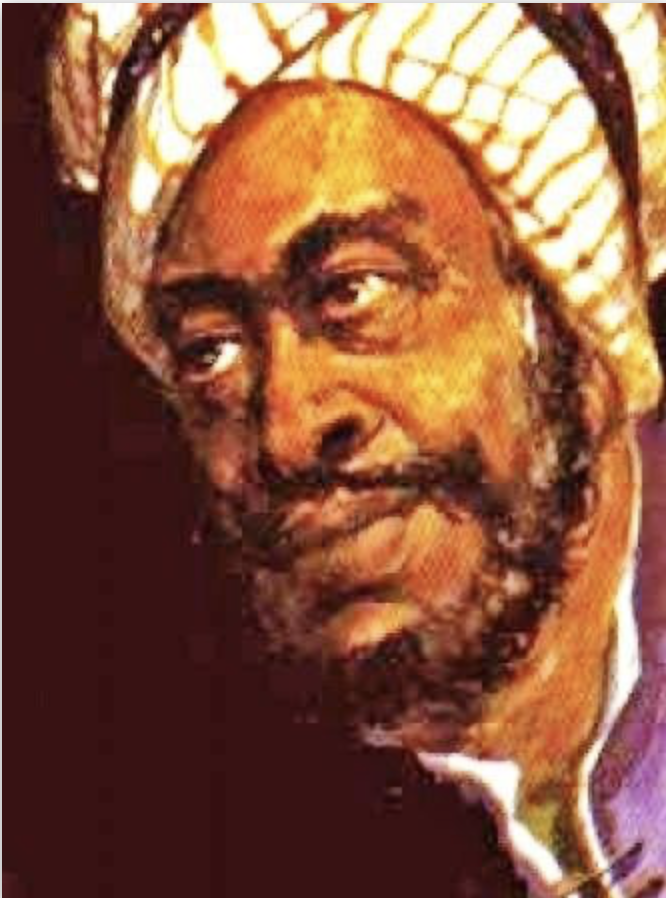

A portrait of Avicenna drawn by Somaiyeh Taheri on a picture of the page of Canon of Medicine which relates to the manuscript.